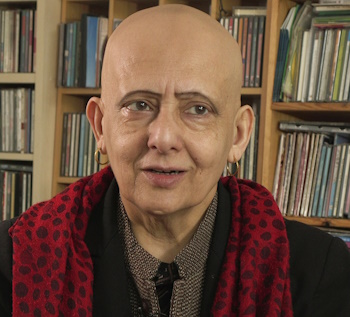

Interviewee: Suman Buchar

Interviewer: Rolf Killius & Lata Desai

Date: 22/02/2025

Address: 6 Eastlake Road, SE5 9QL

SUMMARY

Suman Buchar, a London-based arts and culture professional, shared her journey from

Tanzania to the UK. Born in Tanzania, she moved to the UK in 1972 due to the expulsion of

Asians from Uganda. Her father, a British citizen, was a teacher in Tanzania. Suman

discussed the socialist government under President Julius Nyerere and the cultural

adjustments, including name changes and collective work. She highlighted the integration of

South Asian communities but noted limited interaction with Africans. Suman emphasized the

complex history of South Asians in East Africa and their contributions to African

independence movements.

OUTLINE

Early Life in Tanzania

Suman Bucha introduces herself as a Londoner working in arts and culture, originally

from Tanzania.

Suman describes her early life in Tanzania, attending school there, and the family’s

annual trips to India.

The family intended to settle in India but kept returning to Tanzania due to her father’s

teaching commitments.

The decision to leave Tanzania was influenced by the expulsion of Asians from

Uganda in 1972, making the family feel insecure.

Impact of Socialist Government and Cultural Adjustments

Suman explains the socialist, Ujamaa government led by President Julius Nyerere,

which affected daily life.

The family experienced minor inconveniences like limited access to chocolate and

name changes in schools.

Suman recounts the collective activities and rallies they participated in, fostering a

sense of community.

Lata Desai inquires about the family’s sense of belonging, and Suman discusses her

father’s economic migration and the family’s integration into the local community.

Community Dynamics and Family Life

Suman describes the diverse South Asian community in Tanga, including Gujarati,

Punjabi, Muslim, and Goan groups.

There was less interaction with the African population, but her father was involved in

advocating for African independence.

The family had a swimming club and other social networks, but they mostly

socialized within their community.

Suman reflects on the family’s equitable treatment of their domestic help and her

father’s role in advocating for African independence.

Transition to the UK

The family decided to move to the UK in 1972 due to the political instability in East

Africa.

They spent time in India and then moved to the UK, where Suman’s mother had to

change her passport to British.

The family stayed in Tanga for about nine months, sorting out their new status before

moving to the UK.

Suman recalls the initial adjustment in Norfolk, living with her uncle and attending

school, where she and her sister were the only Asian girls.

Settling in the UK and Cultural Adjustments

Suman describes the initial cultural shock of moving to Norfolk, including the cold

weather and lack of a large Asian community.

She and her sister were placed in lower grades due to their English accent, but they

quickly adapted.

Suman recounts the slight ignorance and curiosity from the local community about

their background.

The family missed their father and the familiar environment of East Africa but

eventually settled into their new life in the UK.

Identity and Cultural Heritage

Suman reflects on her identity as British Asian, influenced by her upbringing in three

cultures: East Africa, India, and the UK.

She discusses the importance of curiosity and exposure to different cultural heritages

in shaping her confidence and self-identity.

Suman mentions her involvement with the Tara Arts Theatre Company, which

sparked her interest in learning more about her colonial history.

She emphasizes the importance of understanding both the positive and negative

aspects of colonial history.

Professional Journey and Advocacy

Suman worked at the Greater London Council (GLC) in the ethnic minorities unit,

distributing grants to community groups.

She later moved into television, making documentaries and working in theatre,

focusing on telling diverse stories.

Suman highlights the need for deeper understanding and representation of the South

Asian experience in East Africa.

She expresses a desire to return to Tanzania to understand her heritage better and to

explore the complex history of South Asians in Africa.

Challenges and Reflections

Suman discusses the challenges of being perceived as a foreigner in India despite her

fluency in Hindi and Punjabi.

She reflects on the importance of self-definition and the impact of her upbringing on

her identity.

Suman mentions the generational preoccupation with identity in the arts and cultural

field.

She emphasizes the need for society to uncover and understand the complex history of

South Asians in Africa.

Future Aspirations and Family

Suman shares her personal aspirations, including winning the lottery and pursuing

more creative projects.

She discusses her sister’s theatre company and the importance of representing their

stories on stage.

Suman reflects on the identity of her niece and nephews, who see themselves as

British.

She concludes by emphasizing the importance of self-definition and the impact of

cultural and historical experiences on identity.

FULL TRANSCRIPTION

Suman Buchar 0:00

So hello. Good morning. My name is Suman Buchar and I am a Londoner now. I work in the

fields of arts and culture and women’s organisation. I was born and brought up in East Africa,

in Tanzania. My dad moved there initially as a kind of a bachelor, and then he got married.

And all me and my siblings were born in Tanzania, and we lived there. I suppose I was 13

when I came to the UK. So a lot of my early life was in Tanzania. I mean, I went to school

there, you know. But because my father was a teacher, what happened was that the he was

allowed to go to India every three years, it got a holiday, and we would go to India every

three years by sea, which was quite exciting and quite an adventure. And then the intention

was always to settle down in India when we got to India, but, and we did make attempts to do

that, actually. But what usually happened was that my dad had to go back to teach. So the

parents, you know, the kids miss the dad, the dad missed the kids and the family, and then

we’d just go back again to Tanga, which is where we lived.

Rolf Killius 1:29

So why did you want to leave Tanga?

Suman Buchar 1:32

I think there was no conscious decision about leaving Tanzania. But what happened at the

time was when Idi Amin was chucking out the Asians out of Uganda in 1972 people, I guess,

in the rest of East Africa, got a little apprehensive about their own situation, as to what would

happen, although perhaps there was no indication of that in Tanzania, because you never got

any sense of that, although maybe things were changing a little bit in Zanzibar slightly. But I

cannot comment on that, because I remember these things as a child. And anyway, the idea

was people did start leaving or thinking of a future beyond East Africa, and my father thought

it would be sensible for us, his children and his wife, to go to the UK, because he was a

British citizen, really. I mean, he had arrived in Tanzania when it was Tanganyika, and it

hadn’t even become independent. So he had come to a British protectorate. I don’t know if

that’s the right word, but that’s when he went to East Africa.

Rolf Killius 2:48

And there was also the issue, there was a kind of socialist, communist government at the

time. Was there an impact on your being there, or your family’s being there?

Suman Buchar 2:57

Well, obviously, when the kids were born, Tanzania, it was Tanganyika. It became Tanzania.

It was run by President Julius Nyerere, the teacher. And it was a socialist, a kind of Ujamaa

government. And I mean in terms of our daily life, you know, we might not have really felt it,

or you might have, I mean small things like, you know, it wasn’t as easy to get chocolate as it

might have been in Nairobi, for example. But we didn’t really eat chocolate all the time, but it

was like a treat. But in terms of in school, as young children, initially, we went to a Catholic

school, then the names changed from like an English name to Swahili name, the nuns

changed from English nuns who left to go to Norfolk, weirdly, which is where we ended up

when we came to Britain. But anyway. But what also happened was that we, we had a little

shamba, little piece of land in school, and we all had to work at it, you know, just things that

were collectively based. And once, once in a year, and Saba, Saba, seventh of July, we’d go to

the public rally, things like that. In that way, a kind of a collective activism of a certain sort.

You know

Lata Desai 4:20

Did you have any sense of your parents, their sense of belonging to Africa? Or would they

have said, No, we are Indians first. And how did that experience? Or did they ever talk about

it?

Suman Buchar 4:35

Well, I think in the case of our family, my father was the first person who went to East

Africa. And he went, I suppose now, we would describe it as an economic migrant, although

as far as I’m aware, he was a young single guy who went to work in Tanzania. How he got

there, I cannot tell you, because unfortunately, both my parents have gone. I mean, how in the

sense of like what took him, did a friend recommend it, or whatever? I don’t know. So we

don’t have the history like other Asian people do, of having a kind of life in East Africa, you

know, earlier, from the 19th century and so on. So I can’t comment on that. In that sense, all I

know was that, as our grandparents from my parents side, I mean, we used to visit them when

we went to India, that we’re from the Punjab area generally, and there was no, I mean, I can’t,

I can’t really speak to to that, what they felt about it, except to say that it was for my father, it

was a good opportunity to get a job. And then, obviously, he had an arranged marriage to my

mum, and she had to follow him across to East Africa, which is where his job was. And I

think it was difficult for her initially, you know, being lonely, like not having any friends

there, not knowing people there, although there was an small Asian community in Tanga,

where they lived, you know, doctors, familys or something like that. You know, a few people

that used to get together. They had a Gurudwara. They had Aryan Mandir, you know. So

there were lots of things like that, places where you could meet your countrymen and women.

Rolf Killius 6:22

I’m interested in the different communities who lived in Tanga, and did you have any

recollection how the community dealt with each other, like the majority black population?

And then you mentioned already you had a Gurudwara and…

Suman Buchar 6:38

Well, as far as the kind of collectiveness of the South Asian community was concerned, I feel

like there was a lot of integration in the sense of the Gujarati, the Punjabi, the Muslim, the

Boharas, the Goans. You know, lot of Goan community as well, but I would say there was

less interaction with African, African people. My dad was a teacher, and he had students, and

sometimes his students used to give us extra tuitions, you know, in maths or whatever. But

mostly as a young child, I kind of rebelled against extra teaching, if you know what I mean,

but I can’t, I mean, I don’t think there was much interaction. But having said that, I mean, I

only know this a little bit, and I have to investigate it more, is that my dad was part of those

group of young people who believed in the independence of Africa. So because he’d been to

Tanzania before it was independent, before Kenya also got its independence, so they were

involved in a kind of a, I wouldn’t call it a radical, radical struggle. But you know, people

who were advocating for the independence of those countries in which they were now sort of

citizens to a certain degree, you know, so, yeah, but generally speaking, in Tanzania, in

Tanga, we didn’t have what you might call a formal apartheid situation of any kind. But yes, I

mean, we went, we used to go to a swimming club, for example, but that was a swimming

club where mostly they were just Asians, and across the road from the sea, you could see the

European Yacht Club, you know. So whatever few Europeans were left in Tanzania in the

60s, you know, they had their own club. So it’s so there was a kind of a separate separatism.

As kids, we used to go to the – it used to be called the Raska Zone Club. I think Raska Zone

is an area in Tanga. And we used to see, you know, from where we were sitting, the sort of

English people going water skiing, you know. And it used to look quite exciting and

interesting, you know, we couldn’t even swim, so we just enjoyed being in the water. So,

yeah, I mean, it was interesting to just see that, but, but we had our own networks of

socialising and so on. I don’t think I met a European person in East Africa in that sense that I

didn’t know anybody actually, apart from the the nuns who were originally in, you know, ran

the school that we went to basically. That’s when I say we, I mean, me and my sister and

then maybe my brothers later, because I think it was a mixed school, you know

But the relationship between the Asians and the native Africans. I mean, how did you…

The thing is, I don’t feel like I’m as hung up about it as nowadays people have a tendency to

beat themselves about it. I feel that we did have a good relationship. You know, in terms of in

our house, there was somebody who worked there the ayaa, let’s say, or whatever, you know,

that is my relationship with her. My parents were quite equitable in terms of treating people .

In terms in my school, I had African friends, you know. We brought them home, and up to a

certain degree, one kept in touch, you know, but then obviously, I left it well over 50 years

ago, my father had his students. He took them to India. There was a bit of a discrimination in

India, not a discrimination, I think, like a curiosity. You see one black person in a sea of 100

of Asians. So, yeah, I mean, the thing is, I feel like nowadays, there’s become fashionable for

Asians to sort of speak about the relationship with Africa and just generally say we were

cruel. They were cruel. I feel like that’s too simplistic an argument. And I don’t feel, I don’t

feel I can buy it in that sense, really, you know, because I know that my father and a few

other families were instrumental in creating the independence, helping to facilitate the

independence of two nations of East Africa. I can’t talk about Uganda, but I know also there

were some Asian people in Uganda in the kind of government. So, yeah, the idea of the

discrimin… the system of layers of, you know, was a kind of, kind of a colonial system that

was put in place, and everybody sort of followed it. So, yeah, anyway, that is my kind of

reflected position. You know, you only intersected in certain shared spaces, if you know what

I mean, you know that is what it’s all about. I mean, obviously I haven’t been to East Africa,

and I want to go and, you know, it’s like 50 years. I did want to go last year, which was 50

years but I feel like I don’t want to just go and be a tourist. I don’t want to just go for Safari.

You know, it’s pointless. In my mind’s eye, I can see the places that we lived in, and it’s

important for me to be able to go in a kind of a proper way, for me to understand it for

myself. Because when we first came to the UK, I saw myself more as a citizen of Africa than

I saw myself as a citizen of India. And that is not because I didn’t know anything about India.

I think I know enough, and I know my own background and everything, but it was more like

we had grown up there, and we were also different to our cousins in India, let’s say. But you

know, over the years, those views change and fluctuate. And now I do feel a huge part of my

heritage is, or my upbringing has come from my parents relationship with East Africa. But at

the same time, I know that of Indian background and origin, and I am Indian in a certain way,

you know, but now my definition is British, Asian. It’s very clear to me what it is. I know

these are self definitions, but that’s what it is.

Rolf Killius 12:51

Can you describe when you left, what happened there, on there, how your father came around

and told you really..

Suman Buchar 12:58

So we, I think we left in the early 70s. We went to India for a holiday in maybe just before 71

and then we were studying in India, and the Bangladesh War kind of was going on in the

skies near where we lived. But that’s fine. But what happened was that we went to visit our

father for a summer holiday. I think this would have been about 1972 actually. And this is the

time what is happening with Idi Amin Uganda is going on. And when we went to East Africa,

it was supposed to be just for our school summer holidays, because we were all in admission

in India, me and my siblings, that is one sister and two brothers. And the whole intention was,

yeah, we’re going for a summer holiday. We’re going to come back. But over there, my

parents must have chatted to each other and decided that they’re going to send us to England

because it was a better opportunity for the children and their future. And my father had to

complete his service because he worked in the government. And really, we never went back

to India. So we had a home in India with all our things in there, we just stayed in East Africa.

Then my mother, who was of Indian passport holding citizen, and her the names of her

children were on her passport. So, you know, they had to change it because make her like her

husband’s dependent British I don’t know these, these things. So we spent some time, like

about eight or nine months in Tanga, and occasionally going to Dar es Salaam to get that

sorted out. And we literally just came to the UK. We didn’t go back. So it’s like if you’re

leaving your house here today because you’re going on a summer holiday to Portugal, and

then 10 years later, you come back, it’s a bit like that. It was bit upsetting for the kids,

because it was like, Oh, my things are in my bedroom, so and so. But, you know, you get

used to it.

Rolf Killius 12:58

So what happened to your place there?

Suman Buchar 12:59

Well, we had, we lived in a place called Chandigarh, and we had our cousins who lived next

door. And I think eventually my uncle, sort of, you know, the house would have was rented,

got rid of whatever we had – fridge, this that, the other – you know, the things and the

clothes, who knows, I cannot comment, and some things they did keep. Because eventually,

when we did go to India, like after being settled in the UK for many years. You know, my

mother did bring the odd thing back that was of sentimental value to her more than of any

material value. So, yeah, it did happen.

Rolf Killius 15:32

What happened to this place?

Suman Buchar 15:32

Well, no, we didn’t. We didn’t really own a place. It was, I don’t think it was a culture of

owning places like we didn’t. It was like a rented you know, yeah, so, and we didn’t actually

have one place, I think we’ve stayed in, like, different bits of Tanga, as it were, because it was

mostly rented, rented houses, I think, you know. And then my father did join us eventually,

like, after he finished his service, 20 years service, but he came to England, and he kind of-

you know, when we came here, initially, we went to live in Norfolk. I mean, we landed in

Heathrow on a cold January. My brother remembers the date, and he always reminds me, I

can check on my phone and tell you, you know. But so we met our cousins, our English

cousins, our English Asian cousins, because they were very English to us, we’d become very

Indian by then. In inverted commas, I can’t explain what I mean by that, but hey. So we

stayed for about a night in London, and then we went to live in Norfolk in Kingsley. We

stayed for about a year there, and then my father came and we stayed in London, but he

passed away soon after. So you know, that was the so our lives began in the UK, kind of

earnest, you could say

Lata Desai 16:46

That must have been quite difficult with your mum with four siblings..

Suman Buchar 16:50

Yeah, I think it was, yeah,

Lata Desai 16:52

You know, and as you say, you were more Indian in Britain. Have you any recollections of

what, of what about your your settling period in Britain, in Norfolk?

Suman Buchar 17:05

Well, we actually went to live with our uncle, my mother’s brother. So our mama Ji, as we

called him, and his wife. I mean, they were very good to us, because they put up he put up his

sister and her kids while her husband, ie my father, was finishing off his service in Africa,

which would have taken about another year or so. My father used to teach in a government

school, and I think that if you spent 20 years or so, you were entitled to a kind of a pension or

whatever. So he did want to complete that, you know, yeah. I mean, we went to school in

Norfolk. They were very good to us. We ie my uncle and aunt, but in Norfolk at the time,

they weren’t that many – there was an big Asian community. There was only, there were a

few families, you know, and, yeah, so me and my sister initially were the only, the only Asian

girls in the school. And then I think my brothers, they were the only Asian kids, but they

were younger, much younger than us, so but we stayed for a year there. They put us in, like a

year low, lower, lower, to our age, because they felt that our English wasn’t great. Our

English was pretty good, but I think our accent might have been very different. You know, I

don’t remember, because you had to take a little test in the education authority at that time.

Did you feel any… Did you have any experience of any racism or from from the Britons

living in Norfolk?

Well, I wouldn’t really call it that. I mean, like my uncle and his wife were already settled in

that town, so they were well known to, let’s say, the local community there. In school, I

mean, I would consider it slight ignorance, because the kids did not know very much about

East Africa, where we came from. And, I mean, I, I was surprised at the lack of curiosity

about other cultures, but that was the 70s. I mean, I think it’s very different now. So, so, you

know, we did get asked some really questions, like, ‘Did you live in a mad hut?’ or ‘Did you

ride on an elephant?’ And we thought, ‘No. no, no, no, we have real houses like how you have

them?’But I wouldn’t say, I wouldn’t say, Nothing malevolent, although, having said that at

that time, on the television in the UK used to have programmes like ‘Love thy neighbour’,

whatever and people did use language that you would not use today, and kids, whatever they

hear on television, is what they kind of say again. So I mean, I don’t want to repeat the words,

but, you know, but overall, I quite enjoyed being in Norfolk, and we did miss the, I suppose,

not having a huge Asian community, because we had been grown up, grown up in that way. It

was a different kind of schools.. first, it was so cold. We hated the cold. We never got used to

it, you know, and all that. And then the culture of going to school, coming home, watching

telly or whatever, you know.

Lata Desai 20:10

Did you miss India and Africa?

Suman Buchar 20:13

I think we missed our dad, really, you know, pretty much. But I think although, I mean, I

haven’t really thought about it, and I was not able to articulate it then, is that we did have a

sense of it’s not something that we could go back to, you know, it’s not like a summer holiday

that you could just rush off.

Lata Desai 20:32

How did your background and upbringing shape yourself and your challenges and struggles,

which you would have had over the years? How do you identify yourself?

Suman Buchar 20:42

Well, I’m British, Asian, as I’ve said. And obviously I know where I come from. I know what

I look like and everything like that. I feel like, you know, I sort of grew up in, you know,

we’re a middle class family. We have education, but no money, kind of thing, you know, but

our parents were in inverted commas, you could say ‘liberal’, you know, like we were not hit

as kids or anything like that. We were encouraged to be adventurous, to have a spirit of

curiosity, to find out things, encouraged to be friends with everybody. And we had our own

innate sense of self, you know. And because we have grown up in three cultures, like in East

Africa, in India and in the UK, so we were exposed without anybody having to teach you to a

lot of different kind of cultural heritages, to a lot of people of different races and languages.

So, yeah, I mean, I think that sort of gives you, in a confidence in yourself, in being able to,

you know, speak to everybody else. The rest of it depends on your character, about whether

you feel you’re shy or quiet person or, you know, like you don’t, whatever, much more

gregarious, you know, that kind of thing . When you lived in East Africa or Tanzania, in our

case, you know, you sort of know a bit of the history from just seeing the people like the

Marabous or the Arabs used to be there. For example. You know, the Africans were there.

The Indians were there. But you do not analyse it or figure out, you know, why is there? Or

you look at the buildings, you know, and they come from a different period of, like, different

centuries. So in that sense, you know, the past is part of the present. So you do not really

think about it. I don’t remember in school in Tanzania, if I had learned about that, and

because it was quite a young country when we were growing up there. And it was 1961 is the

independence, you know, of Tanzania. So when you’re going to school seven and eight, I

mean, that is like my age. I’m as old as Tanzania in that sense. So, so seven or eight year old

countries thinking about the future and rather than the past. So I feel like, in that sense, you

know, it wasn’t something that we looked at in an inquiring way. It was just there. But it’s just

that, when we came to the UK and we got involved, like with a theatre company called Tara

Arts at the time, the whom we met fortuitously after we saw them doing some sketch Diwali

sketches at Wandsworth Town Hall, after we had settled in in London. Is then we asked

Jatinder Verma, who was one of the founders of Tara, and he ran it. And we knew that he had

studied history, that if you could give a few of us that used to go to the group, you know,

some lessons in our history kind of thing. So that’s when we started being, let’s say, more

questioning or curious, or wanting to know more about our colonial past, our shared histories,

or things like that, really

Rolf Killius 23:56

A little bit up to today. You know, do you feel starting in your school? Do you think it was a

kind of here in this country? Do you think there was a kind of teaching in colonial

background and the history of the colonies? You know, UK, you came from a colony. First it

was a colony.

Suman Buchar 24:13

Well, we, I mean, I went to the school in, say, the 70s in the UK. I did enjoy my school,

generally speaking, it was a mixture of like I did do history. So it depends what was on the

curriculum. I did a lot of the Tudors and Stuarts and that kind of history, which was

interesting to me. You know, in terms of doing history, about what I did, the Italian, you

know, the Italian unification, things like that, French, whatever it is, more that when I went to

got to university, you could pick the modules like I wanted to study history, which I did so I

was able to pick, I picked, like, South African history, which related to the Indian Indentured

labour in South Africa, Indian history partition, by which time we had also been starting to go

to Tara Arts Theatre Company. And you know, you got to know in a much more analytical

way about the partition of India, even though, you know, your parents kind of lived through

the partition and experienced it, but you didn’t really ask them any questions, because that

nobody really had wanted to talk about those things in that time. So, so I feel like I chose

what I wanted to study. So from that point of view, I was interested in my history, let’s say so,

so I was able to access it, but we had a good teacher in Jatinder, like in the sense that also to

read books, you know, Romila Thappar, in those days, would have been a big writer, or, I

can’t even remember the name Basham, the one that was India, you know, like we were told

about all these writers by somebody who was giving us a bit of knowledge about it, and the

rest of it depended on our curiosity, like we either went to the Commonwealth Institute

library, which had, let us say, special subjects, or you try to ask your local library if they had

any books. Obviously, it is better now in that the children have opportunity in schools to be

exposed to a wider range of history and global cultures than we were in that sense. But I don’t

feel that I should have been able to swap one for the other, because I feel again, that’s a really

very big, nuanced conversation. If I didn’t learn about the Tudors, Stuarts and learned instead

about the black hole of Calcutta, for example, would that be better for me, I don’t know, you

know, I can’t really say it’s too simplistic to say either or, you know, it’s good to know about

both. But also, what is good to know about is the analysis that we’re having now. And some

of it isn’t like decolonizing the museums as well. It’s like the interpretation, you know,

children today are being exposed to the so called Naive interpretation of how wonderful it

was as well as how horrible it was. So I think that’s a better way of being, you know.

Lata Desai 27:10

There is lot of discussion about Migration Stories on this. You know, present day migration.

Do you see any parallels to the experiences of your parents and your ancestors to what the

present migrants in Britain have?

Suman Buchar 27:27

yeah. I mean, I think, you know, some people are economic migrants, some people are

migrants out of necessity, like what happened to the Ugandan Asians, you know, Syrian

people leaving stuff like that. You know, Afghani people having to leave with the Hong

Kong Chinese, yeah, you can see, you can see parallels to in that way, you know, I don’t

know, is there, like, what would you like me to focus on, you know? Or even, yeah, or Yeah.

I mean, there are, there are parallels, and they are, they are similarities in that sense, you

know, because, or even in terms of the historical experiences, you know, we talk about the

partition of India, stuff like that. But you can think now the partition of Israel, Palestine, you

know, that’s like a such a current big story. Or you can think about the partition of other

nations in the MENA region, you know, which are all as a result of colonial histories. And

we’re all trying to understand it, and, you know, figure out how we can live together in a way.

You know, I can’t claim to understand all of it, but yeah, you know, I think we had curiosity.

Me, my sister, you know, to Shaheen, another actress who was there, you know, a few other

people who used to go when it was what you might call still a community theatre. And

because we wanted to know, and he knew a lot, so we did ask him to give us some insight

into it, and then the rest of it was like, as we went to University College, this, that and the

other, we just expanded our our thinking, or our mind, or, you know, in that way.

Rolf Killius 29:15

And you thought, in a way at the time, that theatre was kind of important for you as a kind of

empowerment,

Suman Buchar 29:23

yeah. I mean, I think we all joined theatre at that point because we wanted to say something,

and it was like a vehicle that we just saw, and something clicked in your head, like I saw

some sketches in about diva in Diwali time at a function in Wandsworth Town Hall and the

sketches were about younger generation, talking about intergenerational action, talking about

the relationship to Britain. You know, they were like small sketches, and you just looked at it

and thought like, that is saying what I want to say, or what I’m thinking. How do I find out

more about this group? And there were some people there, you know, Praveen Bahl, like one

of the founders. You know, you just spoke to them. You discovered that they used to meet in

Milan Centre in Trinity Road. And we just started going.

Rolf Killius 30:09

And you started explaining you studied history, and how did it go on? You finished your

studies?

Speaker 1 30:14

Yeah, so when I went to university, I did, I did study history and classics. I was interested in,

like, Greek and Roman history, but, you know, in terms of the context of Indian history and

South African history and so on, yeah. I mean, I got a degree, but like, my working

environment and my degree is, like, very is kind of different. You know, I initially ended up

working at the GLC, the Greater London Council. But the 80s in the UK or in London also

were quite interesting in terms of activism of Black and Asian like arts and cultural or social

activism. And in those days, the word Black was a kind of a political term which was not a

skin not a colorist term. It was. It was associated with, I suppose, the politics of colonialism,

you know, in that sense. So, yeah, so in that way, you know, we got involved in different

things. So the history came out. In that sense, ‘We are here because you were there’ became

the slogan of the times.

Rolf Killius 31:22

What did you do in the GLC? What was your role?

Suman Buchar 31:24

Oh, I was a Grants Officer or something. I ended up working in I got a job in a unit called

the ethnic minorities unit, and I joined the GLC at a time when the ethnic minorities unit was

celebrating anti racist year. 1984 was anti racist year. So I think my role was to give grants to

different community groups. I was in a team. I was just like, not a unilateral but, you know, I

was in a team of people. It was my first proper job after university. Yeah, it was quite

interesting, you know, exposed me again, to a huge sort of cultural you know, like what was

going on in London with different kinds of groups, what people were doing, from cultural

groups in languages to people running supplementary schools for Black and Asian kids to be

have extra tuition in order to be able to pass O levels, things like that, you know, lots of a

variety of stuff, yeah.

And then the GLC was…

Yeah, and then, and also, just to say, well, and also in the arts and cultural thing, you know,

to give grants to support the sort of individual ideas of cultural groups that came from the

black, the Asian, you know, the different kind of communities, whether it was film culture,

whether it was painting, visual culture, whether it was theatre and so on, you know. So, yeah,

I did work in there until it was abolished by Margaret Thatcher, I think, at the time, you

know. And then there was a another unit that was created by about eight of the London

boroughs to try and run some of the ideas that the GLC had put across. But that only lasted a

short while. And then I got involved in television, like making documentaries, things like

that. You know, you pursued the interest in the arts and cultural area mostly.

Rolf Killius 33:26

Can you elaborate a bit on this? What you have been doing till today at the professional

level?

Suman Buchar 33:32

Well, I think that mostly trying to pursue arts and culture. So for a while, I worked with two

companies like one is was a workshop called Retake Film and Video collective, which is like

the only South Asian franchise workshop, because even in the 80s, people couldn’t just make

films in some way. You had to have a union card and so on. But I wasn’t, I wasn’t part of the

core group of workshop people, but what I did was I set up and facilitated courses around the

history of Indian cinema, the history of world cinema, because it was of interest. Again, there

was a growing interest from young people at the time, and then eventually moved into

making documentaries for television, Channel 4/BBC as part of an associated company there

called First Take Limited and alongside it, also being involved in theatre, because my sister

then set up a theatre company, you know, so we have followed the arts and cultural field in in

a very active way, because the drive came from being wanting to tell your own stories,

wanting to have representation in and wanting to be put across the narratives of stories that

are really not well known. And now you could say, 25 years later, people are more openly

talking about the partition of India. We haven’t actually talked very much about the East

African experience of the… sorry of the South Asians in East Africa. We really haven’t talked

about it much, because it just gets put into this simplistic character characteristic of ‘the

Asians were horrible to the Africans’. But in terms of arts and culture, I’ve only seen like one

or two plays in that context happen. And, you know, we don’t really know. I wouldn’t say I

know much about that experience in a deep way, and I am interested in knowing about it.

You know what took a person to go in a Dow, D, H, O, W, sail on the Indian Ocean and the

Arabian Sea, to end up in East Africa from Diu or Daman in India. What? Why? You know,

why subject yourself to that, and then to work on the railways or and then, I don’t know. I

mean, like, there’s just so much there that we don’t really know about, and then to be, to be

treated terribly when the nations became independent also. I mean, think about what

happened in Kenya in 1968 as well. So, you know, I think it’s a complicated history, and we

haven’t really talked about it in a deep way, and we should, but even I’m ignorant of it, and I

want to know more about it, which is why I want to go back to see my home in Tanzania, but

I don’t want to just rock up in that way and go on safari. I’ve never been on Safari. That is

sad, isn’t it? We lived in East Africa, but we didn’t do the touristy things. We just lived there.

Lata Desai 36:36

What do you think should change in society? I mean, you talked about that we should tell our

stories, and do you have any fears or challenges which you would come across your way if

you were going to dig further stories?

Suman Buchar 36:49

I think the story of the relationship of the Indians or the South Asians in Africa is much more

complex than we think, and their relationship with African Africans, right? We, we know a

little bit about South Africa, because obviously Gandhi was there. There was a lot of

discrimination. There was apartheid in a formal sense of the word, you know, and everything.

And then there is the simplistic kind of rendering, you know, the Asians did not mix. They

did not marry Africans, etc. But there are the odd stories where people did do that. So but

also in terms of the political struggles, I think that some Asians were involved in the politics

of the independence of East African countries. Let us say yes, there were some people

involved in business and that kind of stuff as well. So I don’t think there’s a fear, but I feel

like we do need to uncover it. I mean, I was reading in the Sunday Times of last week, there

is now a Kenyan mayor in somewhere in Northern Ireland, and she said the food that they eat

is chapatis nyama, which is meat and kachumbar, which is like a tomato and onion mix. Now,

chapati in Kachumbar sounds like Indian words to me. So somehow the cuisine has ended up

being part of African cuisine. Now, so I’m curious about that, you know, how did that

happen? You know, I don’t remember that happening when I was there, if you know what I

mean, but so, so, yeah, I don’t think there’s anything to feel like it would be quite exciting to

know, you know, in that sense. And if you were a single explorer who left India and went to

settle somewhere, it would have been quite difficult for you as well to just be the one or two

people who initially went there. It’s like the Indians going to Trinidad in the early days, you

know, or to do the Caribbean generally,

Lata Desai 38:45

When you go to India, you said you, I mean, obviously you were young. How do people

perceive you? Do they see you as a foreigner?

Suman Buchar 38:54

Well, obviously, because, in the sense of, they can just have an antenna that can spot you

from the UK. They just have it, even though I can, you know, speak Hindi or Punjabi is

needed so you can try and blend in. But somehow they figure it out. They figure it out. Then

they say, and then you say, no, actually, I’m from Delhi. If I’m in Bombay, I’ll say I’m from

Delhi. If I’m in Delhi, I’ll say I’m from Bombay, you know. But, yeah, whatever, you know

they can so what can you say? What can you do about that? Or your skin is slightly lighter

because you haven’t been exposed to the sun in the same way, whatever your clothes might

be slightly different, you know, I don’t know.

Lata Desai 39:35

But deep down, you feel like you’re an Indian?

Suman Buchar 39:38

Deep down, I feel I am me,you know, I’m a British Asian person, Suman Buchar. That’s me

basically.

Lata Desai 39:44

Where do you call your home?

Suman Buchar 39:45

Now, my home is where I live. It’s kind of here. I’ve spent a lot of my life in the UK. There is

no myth of return. You know, where am I going to go back to? I don’t even think I could

afford to buy something in India or to live somewhere in India, renting wise or whatever. You

know, obviously, I’d like to spend more time there. You know, it’s a very vibrant country. I’d

like to spend time in East Africa. But the question is, what would I do there? Often get a plan

on the beach or whatever, you know, which is not my personality, even though I’d quite like

to go there anyway, India and East Africa, I have family in India more than we don’t have any

family in East Africa. Because, as I said, my father was the only person who went there,

really. Yeah

Rolf Killius 40:35

if you think about the present situation, what do you have any wishes? It could be personal,

but it could also be about what society what should change? What should …

Suman Buchar 40:46

It, where? here in the UK?

Rolf Killius 40:47

Yeah, just some personal wishes.

Suman Buchar 40:50

No, not really. I just want to win the lottery and do more plays. That’s what I wanted to or

make a movie, you know, things like that. But you know, those are like day to day struggles

that one just continues with in that sense, I don’t have

Lata Desai 41:04

You were talking about your sister and her son, her boys, yeah, young teenagers growing up

in the school.

Suman Buchar 41:10

They’re young adults now. Yeah.

Lata Desai 41:12

How do they see themselves?

Suman Buchar 41:14

They see themselves as British.

That’s why I want to do my sister’s show in Croydon, because for hem, their sense of identity

is rooted in their home, which is the UK, really, pretty much, you know, yeah, but I think she

should speak for like her. And the best speaking is, is the play, because it’s, it’s a question that

we all talk Oh, we always like Asians, are more obsessed about figuring out who we are than

any other culture that I’ve come across. And you think, why? You know, you know who you

are, you know? I mean, I’m joking, but you know what? I mean, you know. But it’s a

preoccupation across generations, especially in the arts and cultural field. It definitely is, you

know, yeah. I mean, I think identity is a kind of a self sort of definition, to a certain degree, in

terms of yourself. But yes, of course, when you fill in those silly little forms, you know you

have to pick from the drop down menu. And I try and pick other always, and then I have to

explain what I mean by other but except when you are going in a hospital or the doctor,

because you think, yeah, okay, they they say Asian genes are shit in this kind of way, or

white genes are shit in this way. You know, they have all this kind of scientific rationales for

it all. But to come back like, generally speaking, identity is a self construct thing. So So for

me, my I do see myself as a British Asian, and I mean that because I have been spent a lot of

my time here, influenced by the politics here. And you know, I did consider myself to have

an African identity until a certain point of my life. But after that, I feel like I was not able to,

like, hang on to that idea, because I have not really had a connection in that way, you know,

except that in my passport, it does say where I was born. And that is weird, because when I’ve

gone to America a couple of times, people ask me, where is that place?